Development of the Water-Power Industry in Paris

How did water-power develop in Paris?

Pages

Introduction: Why was water-power important?How do mills work?How did water-power develop in Paris?What kinds of businesses used Capron's raceways?Conclusion and references

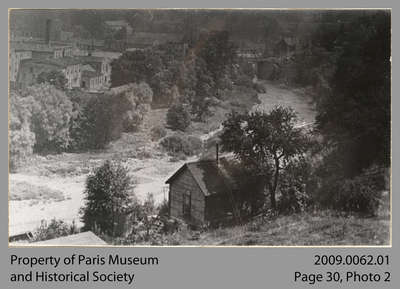

Distillery Hill and Wincey Mill, c. 1900 Details

The first raceway was dug by William Holme in 1824. Gypsum, or plaster of Paris, was the first important business in Paris, and Holme, who owned the grounds where plaster was dug, wanted to increase the output of his mines. When he started his plaster was ground by hand, but this was too slow and painstaking to work well. His first, shallow raceway which cut across the Grand River made it possible to grind plaster mechanically (Smith, 8).

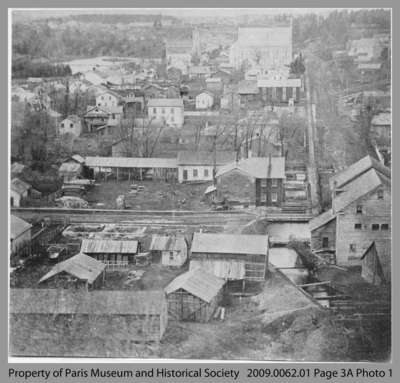

View of Norman Hamilton's mill at the foot of Broadway Street, c. 1878 Details

Capron bought that land from Holme, and in 1830, he built a dam at the end of William Street and enlarged the race Holme had used for his gypsum. This allowed him to power a new grist mill in addition to the existing gypsum mill. This was updated later with a race that went down to the Nith (Smith, 19-20). Around this time, he imported a miller named Josiah Cushman and a land manager to establish and run a new grist mill along this second raceway. He rented this mill first to the land manager, and later to Norman Hamilton, who operated the mills until 1839 when he bought land along Capron’s raceway to build his own grist and plaster mills (Smith, 20).

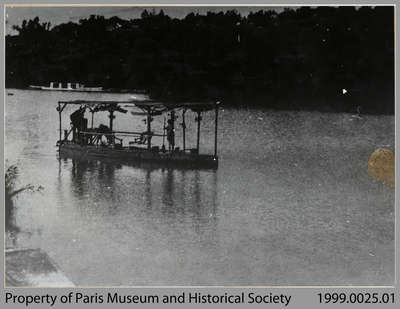

Robert West taking a customer out in his bicycle boat on the Nith River mill-pond, c. 1915-17 Details

By 1838, Capron owned a dam and several races on the Nith River; by 1849, his Nith races supplied 87 horsepower to a number of local industries which depended on machine power (Smith, 88). These raceways could supply power to many types of businesses. These included grist mills (which create flour), sawmills, textile mills, tanneries, iron foundries, and machine shops. Among his customers were many prominent early Paris businessmen such as Norman Hamilton, Asa Wolverton, John Penman and Hugh Finlayson.

Workers by the raceway and waterwheel under the Grand River, c. 1885 Details

Capron sold the land to provide for the creation of the first Grand River raceway in Paris in 1854, capable of providing as much as 800 horsepower and supplying even more businesses (Smith, 88; Paris in 1857, 12, which claims 300 horsepower). These industries included prominent Paris figures such as Charles Whitlaw, whose grist mill on Grand River Street was the leading industry in Paris by 1860 (Smith, 64).

By the end of his life, Capron was no longer directly operating the mills and raceways, but by then the water power infrastructure he had developed had enabled Paris’s thriving water-power industry, and the many businesses which depended on it.

By the end of his life, Capron was no longer directly operating the mills and raceways, but by then the water power infrastructure he had developed had enabled Paris’s thriving water-power industry, and the many businesses which depended on it.