Dark November

by Mel Robertson

DURING THE EARLIER I months of this year, I began a month-by-month series of articles based on things that had happened during each month. However, my wife Shirley's illness and death brought an end to this series and I was not in the mood to start it again. Recently, however, a number of my readers have asked me to continue my series, so this will be my first attempt.

November has been considered a dark month with some particular pre-Christ-mas happenings in the final trip that leads down the road to the Yuletide celebrations. Blackie's Children's Annual of 1915 had this to say about November - "November's here so dark and chill

Fog and mist on vale and hill.

We must carry lights by day

Or we cannot see the way."

Things are not that bad in 1997, but the quick onset of night is a real contrast to the slower evenings of the fall. Children of earlier times regarded this with awe and expectation, looking eagerly to the many festivities of the coming season. This probably does not describe the attitude of children in 1997 for there is plenty of light everywhere, organized outdoor activities and things like TV, computers, electronic games, etc., to keep them interested. For the moment, I will concentrate on the considerable number of things that involved Burford and district during Novembers of yester year. These included the American invasion of Burford, the end of World War I, the great flu epidemic, etc.

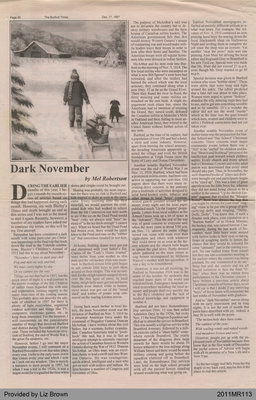

However, before I go into the major November events, I will comment on a Burford November event that takes place every year. I refer to the early snow storm that comes every year and which I note as I look out my window. This is merely a nuisance to most people in 1997, but when I was a kid in the 1920s, it was a major event for it signalled the time when skates and sleighs could be brought out. Skating was probably the most important for there was no rink in Burford and kids wanted to skate as soon as the snow came. Every snowfall, we would question the cold-nosed kids who had walked to school from the 6th Concession one mile north to see if the ice on the Dead Pond would "bear" (why we always said "bear" instead of "is the ice thick enough" I cannot say). When we heard that the Dead Pond had frozen over, there would be quick hikes to the Pond and runs on the "rubber ice" that sometimes resulted in wet feet.

At home, Bulldog skates were got out and sharpened with your father's file. Copies of the "Lady's Home Journal" were stolen from your mother as shin pads and the old hockey stick was examined. In Burford certain little girls began to ask certain little boys to pull them around on their sleighs. This was no easy task for the sleigh runners scraped slowly over the thin layer of snow. In local barns, sleigh bells were got out and horse blankets were shaken while in houses, stove wood was got out of the "wood shed" and kettles of potato soup simmered on the roaring kitchen stoves.

Going back much farther in local history, the main November event was the invasion of Burford on Nov. 5, 1814 by a mounted American force under the command of Brigadier General Duncan McArthur. I have written about this raid before, but it warrants further examination. Canadian historians tend to "pooh-hooh" this raid, but it was in fact an intelligent attempt to seriously interrupt the action of Canadian forces in Western Ontario during the War of 1812. Duncan McArthur, an Ohio man, was an excellent choice to lead a swift raid into Western Ontario. He was courageous, quick-witted, intelligent and a man who got on well with settlers and Indians. He later became a member of Congress and Governor of Ohio.

The purpose of McArthur's raid was not to devastate the country but to destroy military warehouses and the farm houses of Canadian militia leaders. The American government felt that this would destroy Western Ontario's means of conducting war and would make militia leaders leave their troops in order to look after their farms and families. The American troops were all regular horsemen who were dressed in Indian fashion.

McArthur and his men rode into Bur-ford on the morning of Nov. 5,1814. The few local militia who were encamped on what is now Bill Sprowl's west lawn had retreated, and after the raiders had burned the school which was the local armoury, they continued along what is now Hwy. 53 as far as the Grand River. There they found the river in flood, the ferry missing and some militia entrenched on the east bank. A slight engagement took place but, since the Americans had no intention of crossing the Grand, they turned south, defeated the Canadian militia at Malcolm's Mills in Oakland and then, failing to meet another American force, they retired to the United States without further action of any note.

Burford, at the time of its capture, had a population of over 100 and had a hotel, a store and some industry. However, apart from burning the school armoury, the invading Americans apparently ignored the village and even the British headquarters at Yeigh House (now the home of Larry and Donna Cleverdon).

Another notable Burford November event was the end of World War I on Nov. 11, 1918. Burford, which had been a prominent militia centre, had been very active in supporting war activities. Old papers show that there were many recruiting-drive concerts in the armoury plus a multitude of activities designed to send hand-knitted socks, tobacco and £S to local "boys" overseas.

moury every night and the local paper published much "Up the Empire" propaganda. Letters from local soldiers in the Armed Forces took up a lot of space in the "Advance". Thus the end of the war was of great concern to everyone and, when the news came at about 5:00 a.m. on Nov. 11, almost the entire village turned out, some with coats over their night-shirts and others with whatever they could throw on as soon as the factory whistle and the church bells began to spread the glad news. Partly-dressed adults gathered on the main corner to sing hymns accompanied by Millicent Weaver's mother with her accordion. It was a day to be remembered.

However, it was not all rejoicing, for Burford in November 1918 was in the midst of the terrible flu epidemic that touched many parts of the world and killed millions. Emergency hospitals existed everywhere including the local armoury and people died very quickly due to the flu's virulence and the lack of medical knowledge and equipment to combat it.

Burford did not have Remembrance Day services (Nov. 11 was then called Armistice Day) in the 1920s, but every Nov. 11 the local Dragoon Squadron saddled up to attend the service in Brantford. This was usually a religious service at the Brantford Armoury, followed by a militia exercise called a "sham battle" somewhere outside Brantford. The yearly departure of the dragoons drew large crowds for there would be about 50 horses tethered to the iron railings along William Street and there would be much military coming and going before the squadron clattered off to Brantford. Later, the Remembrance Day services were held on the high school grounds with all the patient horses standing around wondering what was going OH.

Earlier November newspapers reflected an entirely different attitude as to what was news. For example, the Advance of Nov. 4,1910 contained an item praising local boys for tearing down the local blacksmith shop on Halloween Night and inviting them to complete the job since the shop was an eyesore. Yet another "stop the press" item was one praising Alan Muir for driving the local editor and Reginald Grey to Brantford in his new Ford car. Special note was made that Mr. Muir did not exceed 25 m.p.h. even though Mr. Grey wanted to go 60 m.p.h.

Special derision was given to Burford women who wore "hobble skirts". These were skirts that were long and tight around the ankle. The editor predicted that a fatal fall was about to take place. Women were urged to ignore "fashion", abandon the silly mincing steps they had to use, and to get into something sensible and to be sensible. (It's a wonder the editor did not use the word "manly" which at the time was the goal toward which men, women and children were to strive.) Political correctness had not yet taken over.

Another notable November event of earlier times was the preparation for Sunday School and "Day School" Christmas concerts. These concerts were major community events before there was a "Net" to be "surfed" by children and before "Beavis and Butthead" presented the intellectual goal toward which children aspire. Every church and every school had a Christmas Concert and every adult parent was determined that every child should take part. Thus, in November, the well-thumbed books of "plays and drills" were brought out and participants began to be "sized up". This was a time of great apprehension for little boys for, whereas they did not mind being chosen to be a soldier in the annual "Up the British Empire" pageant that rivalled the "Manger was always tear that

you might be chosen for your loud "singing" voice to be put into a group of girls carrying dolls and singing, "Dolly, Dolly, Dolly". You knew that, if such a disaster took place, your reputation as a "fearless hunter" or as Howie Morenz, the hockey star, was ruined forever. Consequently, during the last week of November, most little boys went around with furtive looks in their eyes or faking limps or coughing spells to lessen the chance that they would be selected for some "unmanly" part in the coming concert. No one rushed home from school lest they run into a committee meeting in the parlour where the concert was being planned. No one volunteered to do anything but pull the curtain and we all braced ourselves to face the final "D-Day" when there was no retreat from participation in the Christmas concert. I have written a previous article about Christmas concerts of former days, so all I will say is that I doubt if any surviving "boys" of those times will remember the last weeks of November with gladness. And so "dark November" moves along with its early snowstorm and its long nights. It is not the sort of month that poets have described with joy. Indeed, it may fit in well with the poem -"The melancholy days have come. The saddest of the year, With wailing winds and naked woods, And meadows brown and sere." However, people put up with the unpleasant parts of November because they know that in the first week of December the joyful season of Advent will begin with all its promise of a New Life and a New Year.

As the last soggy leaf falls from the big maple in my back yard, maybe this is the place to end this article.