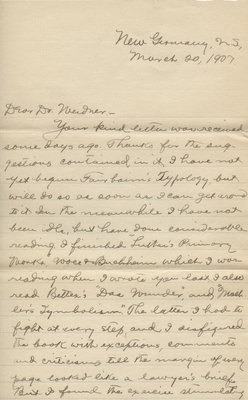

New Germany, N.S.,

March 20, 1907.

Dear Dr. Weidner:

Your kind letter was received some days ago. Thanks for the suggestions contained in it. I have not yet begun Fairbairn’s Typology, but will do so as soon as I can get around to it. In the meanwhle I have not been idle, but have done considerable reading. I finished “Luther’s Primary Works”, Wace & Buchheim which I was reading when I wrote you last. I also read Bettex’s “Das Wunder” and “Moehler’s Symbolism”. The latter I had to fight at every step and I disfigured the book with exceptions, comments and criticisms till the margin of every page looked like a lawyer’s brief. But I found the exercise stimulating

(Page 2)

and enjoyable – excellent intellectual pugilism. It gave me a much clearer idea also of the Catholic view point and of how the came by their heresies. Though, of course, Moehler is a little out of date. If he had lived after the Vatican Council, he would doubtless have changed or modified some of his views. He writes in an irenical and rather amiable sort of way, and evidently would like to be just and fair. But he can’t altogether subdue his partisanship. It crops out especially in the charge which he brings against Luther and repeats ad nauseam, that he held the Flaccian heresy. And the strange thing about it is that while he testifies that Calvin used the same sort of expressions on this point he acquits him of the charge. During the reading of his views on the Church, I read through your little book on Ecclesiologia, which helped me greatly in the refutation. I note that Moehler defends the doctrine

(Page 3)

of Purgatory by appealing to tradition only and as a necessity to complete the peculiar Catholic doctrine of justification. One thing that surprised me was the frank admission that the Catholic Church did not agree with St. Augustine on original sin. I knew it didn’t, but I didn’t think Catholics would admit it. Moehler would also like to see the use of the cup made optional. His defense of its withdrawal is especially weak. The fundamental error throughout the whole book is, of course, the elevation of the Church above the Scriptures, thus setting up a false standard of truth. Luther’s description of faith in Introduction to Romans, he commends, but characterises it as in “The most amiable contradiction” to his theological system. The author's sense of proportion is somewhat questionable. He gives about 40 pages to a consideration of Emanuel Swedenborg, his visions and views – which is far beyond his importance. The object

(Page 4)

however seems to be to show by the testimony of Swedenborg’s angels that the Reformers generally failed to reach heaven. Luther will probably get there eventually, while Melanchthon is left in purgatory without prospect of release and Calvin is unceremoniously hurled into the pit. But to give a thorough criticism of Moehler’s book in a letter is out of the question. I will therefore let up on him for the present. Bettex’s little book is quite good and very suggestive. But he carries his point almost too far, virtually making miracles consist in our ignorance. I notice also that he is an advocate of creationism, which I do not consider reconcilable with the doctrine of original sin. I am still at work on Godet’s John, but am progressing slowly, finding time only for a few verses every day. One cannot but admire his reverent treatment even when one cannot agree with him. I am about half through the second volume. I am also con-

(Page 5)

tinuing the study of Zezschwitz’s Christenlibre, and have read down to the middle of the 2nd Article of the Creed. I was especially pleased with his treatment of the first article of the Creed and the constant connecting of it at all points with the view point of redemption. It is wonderfully clear and instructive in that particular. I note, however, that on the person of Christ, he is a little off as so many even of Lutheran theologians are. He makes the incarnation itself a part of the humiliation of Christ. But I find the greatest of help in this book. It is so full, thorough, clear and logical. I am also reading another book which I find quite helpful, especially as I got little along that line in the Seminary; and that is Robins’ “Ethics of the Christian Life”. Robins, I think is a Baptist and in many points I do not at all agree with him, but he furnishes plenty of food for thought.

(Page 6)

He is too subjective. For instance, he makes the divine law implanted in man’s nature as the standard. Of this even the Ten Commandments are only an outward and partial or fragmentary presentation. And this subjective law it was which Christ came to fulfil and not to destroy. In accordance with this view, the objectivity of the final judgement is [d?] and the same is made purely subjective. Christ in His humiliation has divested Himself of himself of His divine state and is consequently peaceable, the temptations of the two Adams being in every way perfectly parallel. The only difference is in the different results. And yet, strange to say, the author in considering Christ’s emotion as He wept over Jerusalem declares that He here “transcends His status as a mere man”.

The author also adopts the new Presbyterian dogma that all infants dying in infancy are saved. But he declares it is not logical to stop there

(Page 7)

and adds to the list practically all irresponsibles, thereby to all intents and purposes making “infancy” “idiocy”, “congenial insanity”, and “inherited abnormality”, saving means of grace. His application and interpretation of Scripture passages are also frequently at fault, and while he protests against it he cannot escape from a synergising or semi-plagiarising tendency. But I must bring my letter to a close. We have had an exceptionally cold winter, so everybody says. But I have not found it very trying. I rather enjoyed it. We had it so nice for the last week or so, we thought the rough weather was about over. But last night we had quite a snow storm and it is wild and squally to-day. With my kindest regards and very best wishes,

I am

Sincerely yours,

[signed] C.H. Little.