People LIFE STORY The Globe and Mail, July 26, 1999, P.A15

Doctor from Korea practiced in Blind River, Ont.

TAI-YUN WHANG

Doctor, pioneer Korean immigrant, supporter of Korean arts in Canada. Born in South Hamgyong Province, northern Korea, in 1914. Died of cancer in Toronto aged 84.

Dr. Tai-Yun Whang is widely regarded within the Korean community as the first permanent Korean immigrant to Canada.

He arrived in 1948 at a small hospital run by the United Church of Canada in Lamont, Alta. He was supposed to serve a two-year internship, having worked in a United Church mission hospital in Hamhung, northern Korea.

There, beginning in 1939, he had learned fast-paced surgical techniques from the hospital's blunt-speaking but gloriously efficient superintendent, Dr. Florence Murray, who also lent him her medical journals so he could simultaneously improve his knowledge of medicine and English.

Although Dr. Murray had been repatriated to Canada in 1942 in an exchange of wartime detainees, Dr. Whang continued working at the Hamhung hospital until 1944, when the Japanese colonial government expropriated it.

At the end of the Second World War, Soviet and Korean Communists replaced the Japanese as the controlling power in North Korea. Dr. Whang, as a Christian with Western connections, he knew he would not be safe under the new regime, so he joined tens of thousands of other Koreans who fled south to Seoul.

There, he re-established contact with the Canadian missionaries, who arranged for his internship in Canada.

Like many other Korean students who came to North America for what was meant to be a temporary period of advanced training and Western experience, Dr Whang opted not to return to his homeland. The prospect of going back to war-devastated Korea was especially unattractive in his case, since he could not be reunited with his family in the north.

After leaving Alberta and living briefly in several eastern Canadian cities, Dr. Whang established a practice in Blind River, Ont., where he was to remain for more than 20 years.

The move to Blind River was not an immediate success. People did not rush to be treated by the foreign-looking doctor But after he saved the life of a woman who was thought to be dying, other patients began to turn to him.

In time, working day and night, he built a large practice. He would later estimate that he performed 12,000 surgical procedures during his Blind River years.

The practice brought prosperity, and Dr. Whang wanted to share his good fortune by helping impoverished Koreans immigrate to Canada. He contacted Lester B. Pearson, then the member of Parliament for Algoma East. When Mr

Pearson recommended establishing some means of employing the would-be immigrants; Dr Whang invested in a poultry business.

His White Leghorns did lay eggs, and a number of Koreans were able to come to Canada, among them his brother and two sisters. But by his own admission, neither he nor his workers became adept at the new business and eventually he sold it to another immigrant, who did make it thrive.

In 1978, Dr Whang moved to Toronto, where he opened a clinic for family medicine.

Toronto was home to Canada's largest Korean community and Dr Whang became an honoured senior figure within it. But when, in the early 1980s, he made a trip to North Korea by way of Hong Kong — his first return visit to his homeland he temporarily found himself shunned by a large portion of Toronto s Korean community, who regarded any contact with the Communist North as an act of sympathy with the enemy.

During his years in Blind River; Dr Whang had honed his skills in English, and although he still spoke with an accent in old age, he had an impressive vocabulary. He delighted in learning and using the precise word for the things — both abstract and concrete that he wished to describe, and perhaps for that reason took pleasure in having novelist Morley Callaghan as a neighbour.

During his retirement, as chairman of the Canadian Association for Recognition and Appreciation of Korean Arts, Dr Whang devoted a great deal of effort to establishing a permanent collection of Korean arts and artifacts at the Royal Ontario Museum.

At Dr Whang's memorial service, both the Consul-General for South Korea and a spokesman for the ROM paid tribute to his deep and enduring commitment to this project.

The permanent Korean gallery at the ROM will open officially in September, a fitting memorial to a man who carried his Canadian passport and his Korean heritage with equal pride.

Ruth Compton Brouwer, Jae-Dong Han and Young-sik Yoo

Historian Ruth Compton Brouwer interviewed Dr Whang in 1998 while doing research on Dr Florence Murray. Professors Jae-Dong Han and Young-sik Yoo were his friends.

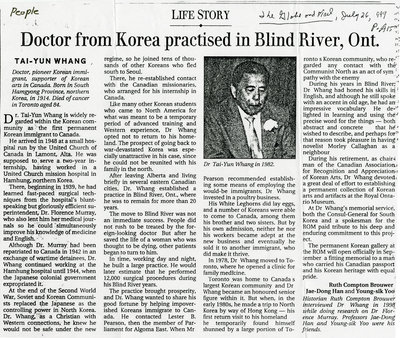

Photo

Dr Tai-Yun Whang in 1982.